Coonan Cross Oath

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity in India |

|---|

|

| Indian Christianity portal |

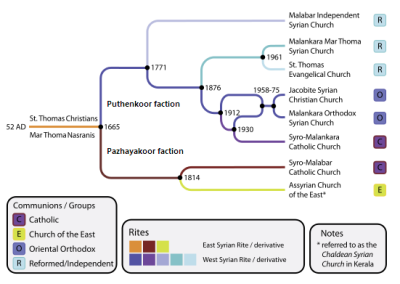

The Coonan Cross Oath (Koonan Kurishu Satyam), taken on January 3, 1653,[1] was a public avowal by members of the Saint Thomas Christian community ofKerala, India that they would not submit to Portuguesedominance in ecclesiastical and secular life. The swearing of the oath was a major event in the history of the Saint Thomas Christian community and marked a major turning point in its relations with the Portuguese colonial government. The oath resulted directly in the formation of an independent Malankara Church, with Mar Thoma I as its head, and ultimately in the first permanent split in the community.

Historically the Saint Thomas Christians were part of theChurch of the East, centred in Persia, but the collapse of the church hierarchy throughout Asia opened the door for Portuguese overtures.[2] Over the course of the 16th century the Portuguese padroado progressively extended its control over the community, culminating with theSynod of Diamper in 1599, which formally brought the Saint Thomas Christians into Latin Rite Catholicism and replaced traditional East Syrian liturgy with Latinized liturgy.[3][4] Widespread discontent with these measures led the community to rally behind the archdeacon,Thoma, in swearing to resist the Padroado.[5]

When news of these events reached Pope Alexander VII, he dispatched a Carmelite mission, headed by Jose de Sancta Maria Sebastiani. This mission, which arrived in 1661, organised a new East Syrian Rite church hierarchy in communion with Rome. By 1662, 84 of the 116 Saint Thomas Christian communities joined this Eastern Catholic Church, known as the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church. The remaining 32 communities eventually entered into communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church(Jacobite), introduced by Mar Gregorios Abdul Jaleel of Jerusalem in 1665. The split into Syro-Malabar and Malankara factions would be permanent; over the next centuries the Malankara Church would experience further splits and schisms.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Background

The Saint Thomas Christians remained in communion with the Church of the East until their encounter with the Portuguese in 1498.[6] With the establishment of Portuguese power in parts of India, clergy of that empire, in particular members of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), attempted to Latinise the Indian Christians.

The Portuguese started a Latin Rite diocese in Goa (1534) and another at Cochin (1558), and sought to bring the Thomas Christians fully under the jurisdiction of the Portuguese padroado and into theLatin Rite of the Catholic Church. A series of synods, including the 1585 Synod of Goa, were held, which introduced Latinized elements to the local liturgy. In 1599 Aleixo de Menezes, Archbishop of Goa, led the Synod of Diamper, which finally brought the Saint Thomas Christians fully under the authority of the Latin Archdiocese of Goa.

However, many Saint Thomas Christians resisted the Portuguese padroado, including members of the old church hierarchy. In 1641 seething tensions came to a head with the ascendancy of two new protagonists on either side of the contention: Francis Garcia, the new Archbishop of Kodungalloor, andArchdeacon Thomas, the head of the old native hierarchy.[7] In 1652 a man named Ahatallah, who claimed to be the rightful ""Patriarch of the Whole of India and of China", arrived in India.[8] He was arrested by the Portuguese and was never heard from again in India, starting rumors that he had died or been murdered.[9] This event combined with Francis Garcia's general dismissiveness towards the complaints of the Saint Thomas Christians, led directly to the swearing of the Coonan Cross Oath.[9]

[edit]Oath

On January 3, 1653 Archeadeacon Thomas and representatives from the community met at the Church of Our Lady in Mattancherry to swear what would be known as the Coonan Cross Oath. The following oath was read aloud and the people touching a stone-cross repeated it loudly:

- By the Father, Son and Holy Ghost that henceforth we would not adhere to the Franks, nor accept the faith of the Pope of Rome[10]

This reference from the The Missionary Register of 1822 seems to be the earliest reliable document available. those who were not able to touch the cross, tied ropes on the cross, held the rope in their hands and made the oath. Because of the weight it is said that the cross bent a little and so it is known as "Oath of the bent cross" (Koonen Kurisu Sathyam).[11][12][13]

The modern Malankara churches all look to this event as the day that their church regained its sovereignty.[9] Those taking the oath swore never to obey Garcia or the Portuguese ever again, and to accept only the Archdeacon as their shepherd.[9] He was ordained as bishop through an unusual ceremnony of laying on of hands, and thereafter acted fully as the metropolitan of Malankara.[14]

In 1665, Mar Gregorios Abdul Jaleel, a Bishop sent by the Syriac Orthodox(West Syrian) Patriarch of Antioch, arrived in India, at the invitation of Thomas.[15][16] This visit resulted in the Mar Thoma party claiming spiritual authority of the Antiochean Patriarchate and gradually introduced the West Syrian liturgy, customs and script to the Malabar Coast.

The arrival of Mar Gregorios in 1665 marked the beginning of West Syrian association of the Thomas Christians. Those who accepted the West Syrian theological and liturgical tradition of Mar Gregorios became known as Jacobites. Those who continued with East Syrian liturgical tradition and stayed faithful to the Synod of Diamper are known as the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church in communion with the Roman Catholic Church. They received their own Syro-Malabar Hierarchy on 21 December 1923, with the Metropolitan Mar Augustine Kandathil as the Head of their Church.

The Saint Thomas Christians by this process became divided into East Syrians and West Syrians.

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Koonan Oath 00001". Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ Frykenberg, pp. 102–107; 115; 122.

- ^ Frykenberg, p. 111.

- ^ "Christians of Saint Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 9, 2010.

- ^ Frykenberg, pp. 134–136.

- ^ I. Gillman and H.-J. Klimkeit, Christians in Asia Before 1500, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999), p.177.

- ^ Frykenberg, p. 367.

- ^ Neill, p. 317.

- ^ a b c d Neill, p. 319.

- ^ The Missionary Register for M DCCC XXII. October 1822, Letter from Punnathara Mar Dionysious (Mar Thoma XI)to the Head of the Church Missionary Society. [1] For a translation of it out of Syriac, by Professor Lee, see page 431- 432. Only the English text is published.

- ^ N.M. Mathew, ‘’Malankara Mar Thoma Sabha Charitram’’ (History of the Mar Thoma Church), 2006. Vol 1 p. 179.

- ^ Dr.C.V. Cheriyan. ‘’Orthodox Christianty in India.’’ 2003. p.199

- ^ John Fenwick. ‘’The Forgotten Bishops’’ Gorgias , NJ. USA. 2009. ISBN 978-1-60724-619-0 p.123

- ^ Neill, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Claudius Buchanan, 1811, Menachery G; 1973, 1982, 1998; Podipara, Placid J. 1970; Leslie Brown, 1956; Tisserant, E. 1957; Michael Geddes, 1694;

- ^ Thekkedath, "History of Christianity in India”

[edit]References

- Baum, Wilhelm Baum; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29770-2. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- Frykenberg, Eric (2008). Christianity in India: from Beginnings to the Present. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-826377-5.

- Neill, Stephen (2004). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54885-3. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

[edit]External links

- Jacobite Syrian Church

- Niranam Diocese of Jacobite Syrian Church

- History of the Orthodox Church

- [2]

- History of the Syro-Malabar Church

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment